By Glenn A. Baker

There is a constant, inescapable sensuality to the entire Cuban experience. For all the crumbling decay, the tarnished and faded glamour, and the shortages and sacrifices of a country whose economy virtually collapsed when the Soviets cut off the drip-feed more than a decade ago, there is nothing dormant or moribund about the place.

Take Latin vibrancy and pride, wind it up a few notches with classic Cuban machismo, stir well with history, intrigue and uncertainty, garnish with a siege mentality, serve warm with Spanish style and you have the very core of the Caribbean, its only truly essential destination.

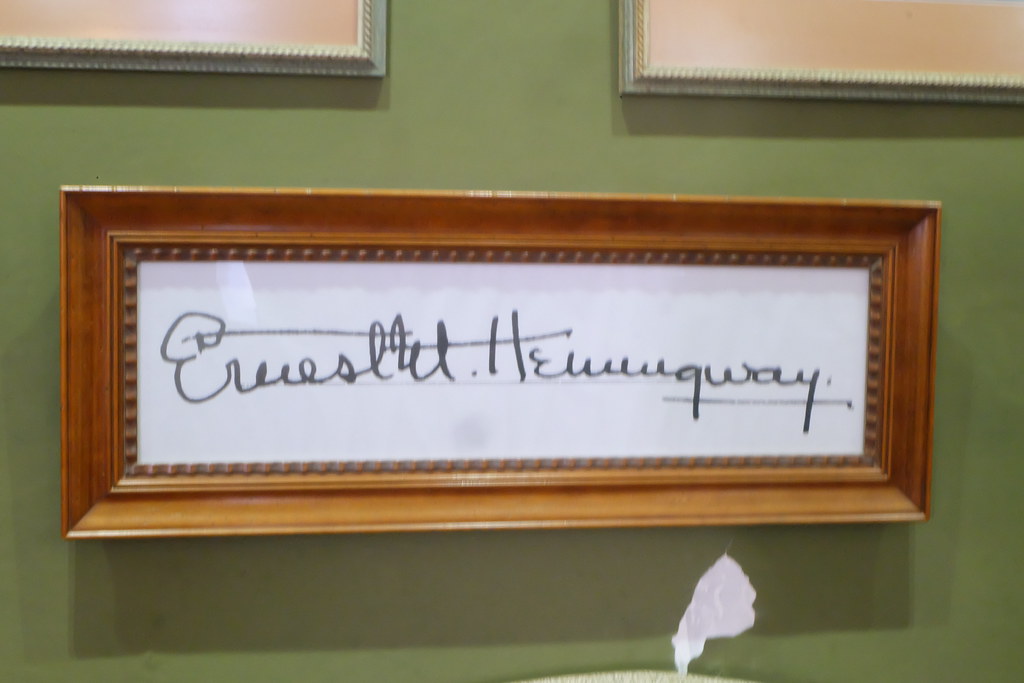

Old Havana offers the ultimate tropical decay - seemingly not a lick of paint applied to most public buildings in 44 years (some of them still pockmarked with bullet holes); barely a discernable civic maintenance or repair programme; streets empty of pretty much anything mobile except fabulous fifties finned wonders from a then-dominant Detroit - Chevvies, Caddies, Oldsmobiles, Dodges and flash Fords held together with wire, spit and unsanctioned prayers; bars with Hemingway’s signed notes pinned to the walls; rusted wrought-iron balconies; clap-board cinemas; amateur Ava Gardner hairdos; and heavy Chinese bicycles probably discarded after the Long March. All told, a glorious decrepitude, a whole nation frozen in time.

That time was New Year’s Eve 1958 when the mobster party that was Havana ended with the arrival of Fidel Castro’s rebels and the overthrow of Bully Boy Batista. The khaki-clad warriors took over a city which was drawing 300,000 eager visitors a year over the Straits of Florida on cheap shuttle flights and car ferries, a city awash with glittering hotels and syndicate-run casinos with entertainment lounges and club rooms booking Stateside celebrities the calibre of Frank Sinatra, Eartha Kitt, Sammy Davis Jnr and Nat King Cole to entertain the bejewelled and tuxedoed high rollers.

Mostly the swanky pleasure palaces were left to stand ... and rot, while Fidel directed his energies to what he saw as worthier revolutionary goals. Today, even he understands their potent allure to the tourists (and their hard currency) he seeks to attract and dust is being officially blown off previously boarded-up premises.

Foreigners of literary bent trawl the cobbled streets of tarnished Old Havana, near the sea-swept Malecon on the edge of the Gulf Stream, in search of the locations and even the characters of a master’s prized works; and they are not disappointed. The old Hotel Ambos Mundos has a street wall plaque in honour of Ernest Hemingway and Room 511, where he began work on For Whom The Bell Tolls, has been retained as a mini-museum, with his old Remington typewriter and an empty bottle of Chivas Regal on display. Martin Cruz Smith, of Gorky Park fame, may not have gone in search of the ghosts of ‘Papa’ but he recently drew on the extraordinary ambience of the UNESCO World Heritage-listed precinct to create his evocative best-seller Havana Bay.

Foreigners of literary bent trawl the cobbled streets of tarnished Old Havana, near the sea-swept Malecon on the edge of the Gulf Stream, in search of the locations and even the characters of a master’s prized works; and they are not disappointed. The old Hotel Ambos Mundos has a street wall plaque in honour of Ernest Hemingway and Room 511, where he began work on For Whom The Bell Tolls, has been retained as a mini-museum, with his old Remington typewriter and an empty bottle of Chivas Regal on display. Martin Cruz Smith, of Gorky Park fame, may not have gone in search of the ghosts of ‘Papa’ but he recently drew on the extraordinary ambience of the UNESCO World Heritage-listed precinct to create his evocative best-seller Havana Bay.All the ghosts are still there, the spiritual pantheon is immense. Visitors do not remain indifferent to the power of the place as they down daiquiris at the elegant art-deco El Floridita on Calle San Rafael (seated, if possible, at the rich mahogany bar near the bronze bust of Hemingway and his own sacred stool). Actor Woody Harrelson did that a couple of years ago when he found a way to take up residence in the grand Hotel Nacional down the way a bit and write songs for a week.

Writers or package tourists, they all inevitably seek out ridiculously cheap boxes of Monte Cristo No. 4’s, locations they think they remember from the Godfather films, vast Spanish forts, the most imposing Cristo Redentor statue outside of Rio, a dot-matrixed image of Che Guevera bolted to the entire facade of a building, a deified boat in a glass case, street markets full of fine old (politically correct) books, a tot or two of the 33 million litre annual rum production, the architecturally-striking Bacardi Building, two dollar meals in private restaurants, and infectious music.

Music is as essential a component of Cuban life as fried pork, cigars and rum, and all the mambo, rumba, cha-cha-cha, cubop, cu-bop Afro-cuban jazz, salso, soca, son and merengue music derived from mountain communities, dance halls and churches was first distilled for foreign consumption in Havana’s sweaty clubs and road tested on its salacious dance floors.

Tourists soon come to realise that, even if they look no further than the country’s premier and essential visitor drawcard, the internationally famous Tropicana cabaret, operating for more than half a century. Opened as a nightclub on New Year’s Eve 1939 it has been described as an “exotic tangle of huge trees, multiple stages and neon lights, where it is impossible to watch all the action at once.”

The action is bold, colourful, sexy and ceaseless, culminating in the Dance of the Chandeliers, which sees the strutting mulatto showgirls parade across the vast main stage attached by electrical cords which illuminate their towering Carmen Miranda-type headdresses. By Cuban standards, it is fearsomely expensive but they come from Cyprus to Columbia to see it and, of the few services that can be said to be guaranteed in Cuba, power supply to the Tropicana is at the top of the list. The lights in the steamy grove of trees never go out.

|

| Musicians on the street of Havana (RE) |

Australians are just beginning to find their way to the large, lush and compelling island sited between the two American continents. Though they really don’t have to go all that way to go the beach, many find themselves reposed and relaxed on the palm-fringed shores of Varadero, which boasts some of the best beaches in the Caribbean, as well as a string of competitive luxury resort hotels.

There is something beguiling about Cuba and its inhabitants, who, against the odds, are developing a credible and plucky film industry (Guantanamera was a delight) and once again exporting music.

In a patronising but enthusiastic 1926 guidebook, a keen celebrity traveller by the name of T. Phillip Terry offered the observation: “The average Cubano is a happy, helpful, songful, tuneful, whistling, pleasure-loving person, non-vicious, of cleanly habits and at peace with himself and the world. Unlike many Latin Americans, the Cuban is slow to anger. Personal quarrels are rare. Malice, envy, contumacy and destructiveness seem lacking in his character. One sees little wrangling, despite the fact that in social matters the people are as ceremonious as the French.”

Though battered by circumstances, the Cubans are still largely as Terry found them between the world wars. It is the pleasure-loving component which has always endeared them to visitors and, one suspects, always will.”

For tours to Cuba, speak to the specialists at Movidas

No comments:

Post a Comment