Words: Roderick Eime

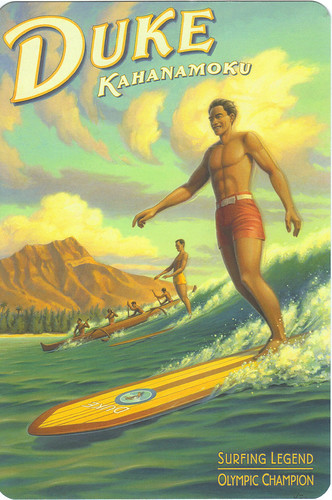

How many surfers do you know with their own statue? Anyone who has strolled, ice cream in hand, along Waikiki’s famous boulevard cannot fail to miss the famous likeness of Duke Paoa Kahinu Makoe Hulikoholoi Kahanamoku. Or, just ‘Duke’, known to all as the father of modern surfing.

The ancient Hawaiians were observed by a curious Capt James Cook who noted in his famous journals that the natives of the Sandwich Islands enjoyed cavorting in the surf with planks of light wiliwili (Erythrina sandwicensis) wood. The longer ones were called alaia and the shorter ones, olo, and it was clear that status dictated who rode the longer ones because trees of sufficient size were rare.

The ancient Hawaiians were observed by a curious Capt James Cook who noted in his famous journals that the natives of the Sandwich Islands enjoyed cavorting in the surf with planks of light wiliwili (Erythrina sandwicensis) wood. The longer ones were called alaia and the shorter ones, olo, and it was clear that status dictated who rode the longer ones because trees of sufficient size were rare.This frivolous, unholy pastime was frowned upon by the missionaries, who arrived at the end of the 18th century. Despite their attempts to stamp out the activity (along with other ancient customs like hula dancing) a few Hawaiians continued to surf in secret and at the time of Duke’s birth in 1890, the sport was still just an indigenous curiosity. But it wasn’t surfing that was Duke’s springboard into the international limelight. It was swimming.

Duke was born into a large family with five brothers and three sisters. Against a backdrop of political turmoil, the family moved from his birthplace, Honolulu, to the seaside village of Waikiki in 1893 where he learned to swim and surf using a traditional olo. Duke was a typical keiki (beach baby) frolicking in the sand and playing in the sea.

“My father and uncle just threw me into the water from an outrigger canoe. I had to swim or else!” said Duke in the biography, Duke: A Great Hawaiian.

“We keikis taught each other.”

His schooling was cut short by a need to earn money for the large family.

“I spent my time trying to earn money – selling newspapers, shining shoes, carrying ice and doing just about anything to bring in some pocket money,” he told Lowell Thomas on one of the famous broadcaster’s radio programs.

With plenty of time in the water fishing and freediving for shellfish, it came to pass that Duke grew into a tall (185cm) strapping lad with an impeccable aquatic pedigree that could be traced back centuries.

|

| “You know, there are so many waves coming in all the time, you don’t need to worry about that. Take your time, wave come. Let the other guys go, catch another one.” – Duke Kahanamoku on life and surfing |

His prowess in the water was unmistakable and in his first swim meet at the age of 21, Duke smashed the world 100 yard freestyle record by an astonishing 4.6 secs using his own special stroke, the “Hawaiian Crawl”. When the times were sent to the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), officials were in utter disbelief and refused to recognise the feat, claiming that a timing error, tides or currents must have assisted the unknown athlete in his open water sprint.

Despite this setback, there were plenty of Hawaiians who believed in this regal young gentleman and a public subscription raised enough money to send him and two others to the mainland USA National Swimming Championships in 1912. He began badly, without proper preliminary training, but quickly recovered to secure himself a place in the US Swimming Team at the Stockholm Olympic Games. Here all doubt was erased and Duke won gold in the 100m freestyle, receiving his victory wreath from King Gustaf V and the nickname "the Bronze Duke of Waikiki."

His swimming feats continued despite the cancellation of the 1916 Olympics due to WWI and at nearly 30 years of age, he won 100m gold again at Antwerp in 1920 as part of a US trifecta with another World Record time of 1:00.4

During the war, Duke was in demand as an exhibition swimmer and surfer and he made a historic visit to Australia just as our young men were heading off to Egypt in preparation for their wholesale slaughter at Gallipoli.

"Kahanamoku is a wonderfully dexterous performer on the surfboard, an instrument of pleasure that Australians have so far been unsuccessful in handling to any degree. Reports have been brought back from overseas of his acrobatic feats executed while dashing shorewards at great speeds, but one doubts the possibility of Duke, or anyone else, duplicating such feats in Australian surf. Still, if he should give one of his rare exhibitions for our edification, be sure it will create a keen desire on the part of our ambitious shooters to emulate his deeds, and it goes without saying that his movements will be watched intently. Personally, I am convinced that the natural amphibious attitude of the Australians will enable one or another to unravel the knack," wrote Australian Olympic swimmer and 1912 Olympic Silver medallist (behind Duke), Cecil Healy in anticipation. Tragically, Healy enlisted in the AIF the next year and was killed in France.

His demonstration at Sydney's Freshwater Beach was remarkable for several reasons. Firstly, it is considered the birthday of the Australian surf culture and secondly, because Duke arrived without a board.

"Having no board, he picked out some sugar pine from George Hudson's, and made one. This board - which is now in the proud possession of Claude West - was eight feet six inches long, and concave underneath. Veterans of the waves contend that Duke purposely made the surfboard concave instead of convex to give him greater stability in our rougher (as compared with Hawaiian) surf,” wrote reporter Patricia Gilmore, as part of a nostalgic retrospective in the SMH in 1948.

"Duke Kahanamoku was asked to select the beach where the exhibition would be given. He chose Freshwater (now Harbord). It was in February, 1915, that Australian board enthusiasts had their first opportunity of seeing a 'board expert' on the waves. There was a big sea running, and from 10:30 in the morning until 1 o'clock Duke never left the water. He showed the watchers all the tricks he knew, sliding right across the beach on the face of a wave. Demonstrating the ease with which he could manage with a passenger, he took Isabel Latham (still a resident at Harbord) out with him, and they would come right into the beach with incomparable grace and precision."

Duke clearly enjoyed his time Down Under and was impressed with our local surf conditions while his natural charm, glamorous appeal and gracious character obviously enthralled all of Sydney.

"I must have put on a show that more than trapped their fancy, for the crowds on shore applauded me long and loud," recalled Duke in his 1968 book, Duke Kahanamoku’s World of Surfing. "There had been no way of knowing that they would go for it in the manner in which they did. I soared and glided, drifted and sideslipped, with that blending of flying and sailing which only experienced surfers can know and fully appreciate. The Aussies became instant converts."

Duke eventually lost his world swimming crown in 1924 to handsome Johnny Weissmuller, later to become famous in films as Tarzan. Duke himself began appearing in films about this time playing, ironically, American Indians. He made 14 films in all, the last, Mr Roberts, in 1955.

In 1925, he hit the headlines again when, employed as a California lifeguard, he and two other surfers paddled out to save 12 fishermen from a boat that capsized in heavy seas near the Newport Beach harbour. The feat was hailed as “the most superhuman surfboard rescue act the world has ever seen."

Duke’s life was full of variety, glamour and, at times, plain honest hard work. Apart from lifeguard duties and occasional movie and TV work, he served as sheriff of Honolulu for almost 30 years until his retirement in 1961.

In 1968, Duke passed away from a heart attack and his burial at sea was attended by thousands of mourners while the motorcade was preceded by a 30-man police escort.

His legacy is enormous, not just in Hawaii, but around the world as the first international ambassador of surfing. So, as you gaze at the muscular bronze statue adorned with leis on the boardwalk at Waikiki, bow your head and repeat Duke’s mantra:

"Mahape a ale wala'ua,"(Don't talk, keep it in your heart)

Reading list:

Duke Kahanamoku’s World of Surfing by Duke Kahanamoku and Joseph Brennan 1968

Duke: A Great Hawaiian by Sandra K. Hall 2004

Legends of Surfing: The Greatest Surfriders from Duke Kahanamoku to Kelly Slater by Duke Boyd 2009

High Surf: The World's Most Inspiring Surfers by Tim Baker 2010

No comments:

Post a Comment